Note: this is not a PSC140 post. Scroll down for my environmental blog contribution for the week of 2/8/2010

I've had a few conversations with friends recently about growing up in a world filled with wizards and magic spells. Somewhere between video games, books, movies, and role-playing, many of us spent our childhoods in the backyard with a

boffing sword, holding off hordes of imaginary Chaos Warriors (yes, I went for the

obscure Hero Quest reference). I've been thinking back on that a bit lately, and I've got a few thoughts about my own childhood that I want to try to iron out here. There are references in this post that not everyone will get, but I'll try to keep it accessible, such that with context clues, you can figure out what I'm getting at (if I haven't already lost everyone with Hero Quest). All references to "Avatar" are to "...: The Last Airbender," not James Cameron's recent film.

First, magic (and other magic-like things, such as elemental control in Avatar) seem to only exist as a backdrop to war. It's especially black-and-white in video games like Final Fantasy or non-video games like Dungeons and Dragons. Magic is a weapon, and nothing else. In an RPG, you would never waste your precious spell slots/points on a spell you're not planning on blasting goblins with. Maybe an occasional spell such as invisibility, so that you can sneak up on a goblin before blasting it. But that's about it.

(Gandalf with his Instant Comedy Sticks. Just add fire!)

In books, the world is typically more complex and developed, but the non-battle applications of magic are still limited. Gandalf makes fireworks for the hobbit children. Avatar Aang amuses children with spinning beads. But it's more for comic relief than any actual plot purpose. Much to my own surprise, the one counterexample I could think of was one of the most pop-culture-ish interpretations of magical worlds: Harry Potter.

The world of Harry Potter leaves room for day-to-day magic use. It's the only system I can think of where there is a spell for cleaning a room. There are magic objects that serve "mundane" purposes, like pensieves, or the Maurader's Map. Sure, they end up being plot-relevant and in the book exist only to further the fight against Evil. But it is made clear that the Maurader's Map was created for common childhood pranks, and that was it.

J.K. Rowling took steps to create a world that is "normal" except for the inclusion of magic, and I think that's noteworthy. It may be part of the reason why the books were so compelling. But at the same time, I sometimes felt like she stopped short, and created a number of spells and items that only existed for Harry and friends to find. The one I joke with friends about most often is the "patronus" (from the third book, but used again later). It appears to serve no purpose other than scaring away dementors. Which are something that the average wizard never ever encounters. Yet, it's set up as an important spell that every wizard would know. There are hundreds of these convenient set-ups in fantasy stories, and we, the readers, wouldn't have it any other way.

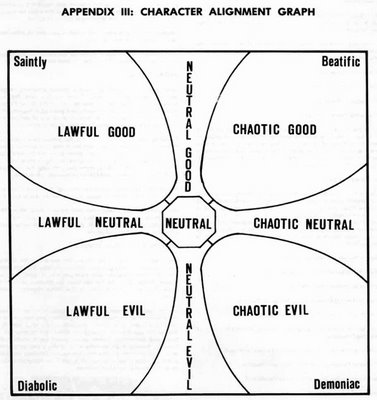

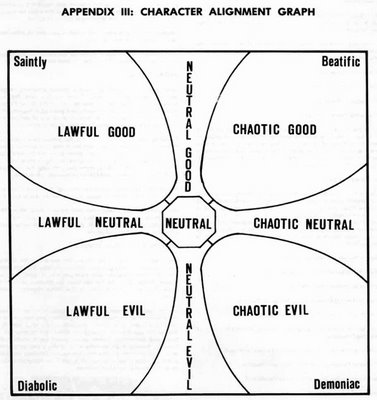

A second thought is that fantasy worlds tend to be completely black-and-white in terms of good and evil. Granted, other genres fall into the same trap, so we're not talking about something unique to fantasy. Still, it's worth noting that we're comfortable with our Saurons and Voldemorts and Kefkas and Firelord Ozais, and the list goes on. One of my

favorite comics points out the limited nature of this setup.

(The classic D&D "alignments")

So, this all got me thinking. What if someone created a comprehensive fantasy world, with as much richness of history and detail as Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter, (or even MORE history, perhaps). Then someone took that world, and *didn't* turn it into a cataclysmic battle of good vs. evil. Would anyone read it? Would it be engaging? Could a non-epic story be told in an epic fantasy setting? If properly written, could it be deep and nuanced? The only thing that's coming to mind right now is a modern Hollywood romantic comedy set in a fantasy world, and that's actually the thing I'd *least* want to see created out of this little brainstorm.

I'm not sure what the solution is, but I know how to define the problem I'm having. Regardless of the medium, the fantasy world is a place where pretty much any action is justifiable if the enemy is "evil" (see comic linked above). And if the enemy is not human, it's even more justified. Maiming evil humans sometimes require a degree of moral turbulence, but nobody ever feels bad for an orc. Again, fantasy is not the only genre to oversimplify good and evil, but it's the one I grew up with. I see fantasy, along with a million other forms of media, as continuing the notion that the world is black-and-white. Without some other counter-balancing perspective, it becomes easy to see criminals as The Bad Guys, rather than human beings screwed by a society we create and control. It's easier to view greedy CEOs as People Who Should Die, rather than people who need a new kind of education.

I guess what I'm asking is this: in a few years, when most of the world has figured out that we've been missing the point for most of human history, and that widespread cooperation, respect and trust are truly the basis of civilization, and that there is no such thing as Good and Evil, and that we are all just People... when all those things happen, what will fantasy look like?